Bigscreen

Supported Platforms: Steam (Vive, Rift, Widnows VR), Oculus (Rift)

Planned for 2018: Oculus Go, Gear VR, Daydream, and PSVR

Unlike Virtual Desktop, which has been a ‘full’ release since March 2016, Bigscreen is still in beta, and it’s free. While both apps enjoy regular updates, Bigscreen has inevitably appeared less ‘finished’, but is also considerably more ambitious. It functions similarly to Virtual Desktop in representing your monitor’s resolution, but offers much more besides, as it is built from the ground up to support multi-user connectivity.

It features customisable avatars with animating hands and mouths, and the ability to host social rooms for up to four users. This allows each participant to see each other’s desktops, and anyone can stream their desktop (along with audio) to the main screen in the room for everyone to view together, enabling virtual meetings, movie viewing, and LAN parties. A ‘Big Room’ mode allows 10+ players in a single room, but works a little differently when it comes to screen sharing.

Compared to Oculus Desktop and Virtual Desktop, Bigscreen’s screen image looks rather soft, even at maximum quality settings. The effect is quite pleasant for moving images, but it isn’t the best for text. It has support for 3D movie formats, but doesn’t offer a spherical video player.

Over the past year, it received many updates, including an avatar creator tool, a 3D drawing marker, and a massive cinema room. It used to lag behind Virtual Desktop in terms of gaming performance (when using it to display a non-VR game), but multiple performance improvements to Bigscreen has closed the gap.

Windows Cliff House

Supported Platforms: Windows “Mixed Reality” VR

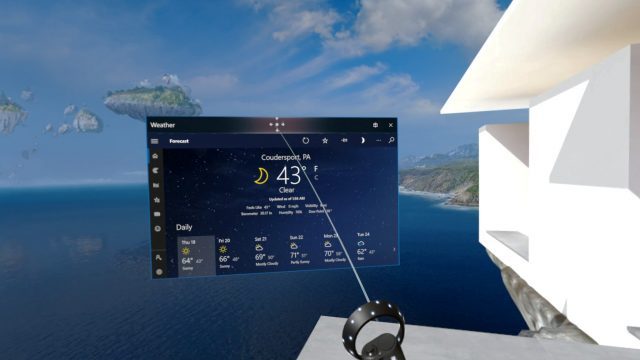

The ‘Windows Cliff House’ is the default ‘home’ environment you’ll get dropped into when donning any Windows VR headset. The space acts as both a launcher into immersive applications, but also as a 3D interface for your desktop. When you press the Start button you’ll see a floating Start menu listing all of your UWP apps, any of which can be popped into a window which becomes a floating screen in in the virtual environment.

Unlike other virtual desktop offerings, the Windows Cliff House allows you to create a completely customized 3D desktop environment by placing application windows in physical locations within your virtual home. So for instance, you could choose to have a ‘media room’ where you put media applications like a video and photo player, and a ‘web room’ for browser windows with all of your social content—then you actually navigate between the two by moving your avatar around the environment, rather than clicking buttons. It sounds strange, or maybe even unnecessary on paper, but there’s something very natural and intuitive about ‘physically’ organizing various modes of desktop computing in this way.

Windows are easily arranged and resized with motion controller support, and usually snap into logical places (like against walls). You can point your teleporting cursor at a window and be helpfully teleported into an ideal viewing distance for that window, based on the window’s size and position.

Microsoft has built the Windows Cliff House right into the Windows operating system, which brings a number of benefits, including deep integration with Cortana for voice control, allowing you to do things like launch applications, close windows, and make selections with just your voice. The Windows Cliff House also employs a floating keyboard with helpful features like word prediction.

For true desktop-like usage, you can use your keyboard and mouse rather than the Windows motion controllers. This of course makes typing much more practical, and Microsoft has done a pretty good job of allowing you to use your 2D mouse to interact with the 3D environment for things like moving and modifying windows, and using the applications therein. One annoyance for now is that when using keyboard and mouse it’s more difficult to locomote around the environment due to some wonky controls (hold right click to initiate teleportation, rotate the mouse wheel to change direction).

– – — – –

When it comes to true, desktop-class productivity using a virtual reality desktop, the hardware limitations of the first generation of headsets remains a hurdle. In the majority of 3D environments, particularly when gaming, the feeling of presence quickly overrides most qualms about image quality. But when I’m simply sitting at the desktop trying to get stuff done (no matter which app I was using), my awareness of the resolution limitation rarely moved to the back of my mind. And there’s only so much that supersampling and other anti-aliasing solutions can do.

Text is the main culprit, which is far removed from the fidelity we take for granted on high pixel density displays on our mobile devices, and even on our desktop monitors, which have a much greater pixel density per degree than the VR displays that are placed so close to our eyes and then stretched out across a wide field of view. This is somewhat alleviated by the freedom of window placement; you can bring elements up close for perfect text readability, or push them so far away that (in some cases) it looks like a distant, twinkling star. Playing around with the extremes is novel, but there is only a limited range of depth that has any practical use, and it’s tedious to have to bring elements so close all the time.

True productivity in a virtual reality desktop certainly has a long way to go, but we’re glad to see four worthwhile options already out there and continuing to improve.

Update (1/3/18): We’ve fully revamped this article after taking a fresh look at the ecosystem of virtual reality desktops now available to VR headsets. The prior version of this article included the VR desktop apps Envelop and Multiscreens—while Envelop’s technology was impressive—as was its millions of dollars of funding—sadly the company ceased operations in early 2017. Multiscreens offered some of Envelop’s functionality in a rather less-polished package, and while it is still available to purchase on Steam, it hasn’t received an update for over a year and may never leave its Early Access state.

Additional reporting by Ben Lang